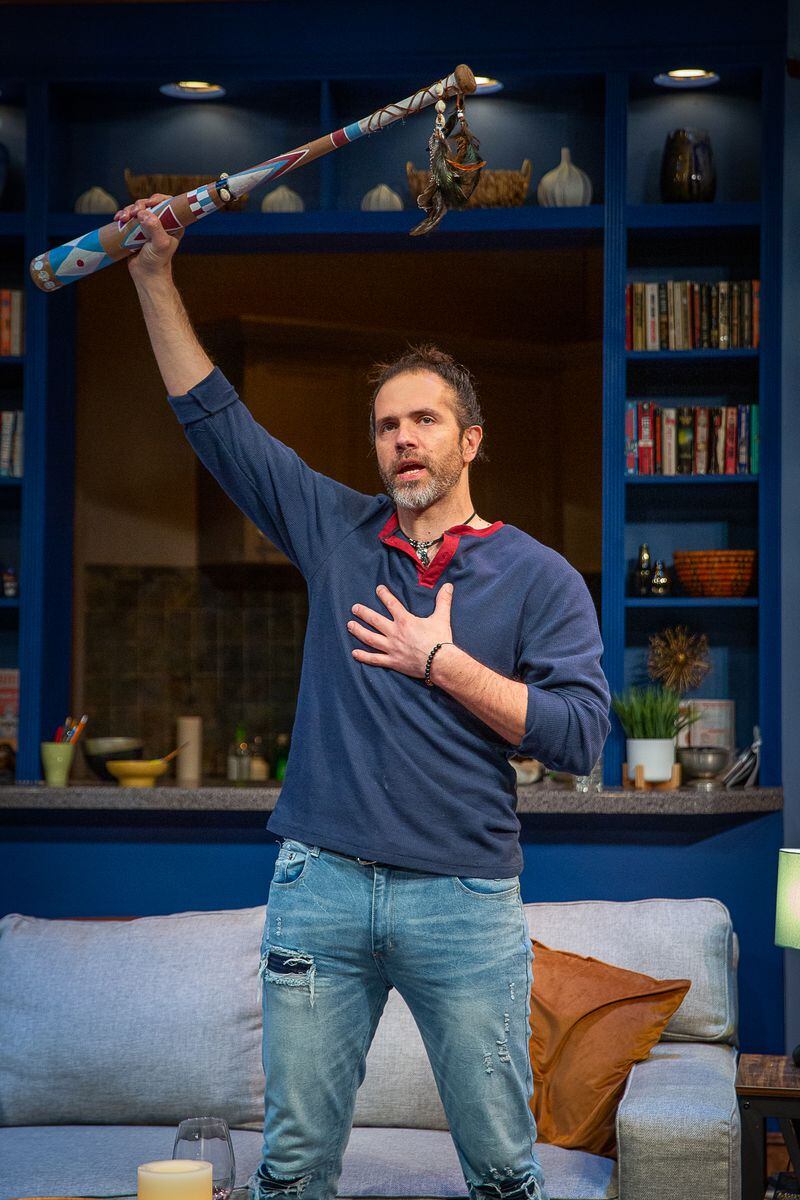

Anatole (Jordan Patrick) and Natasha (Alexandria Joy) have great chemistry in “Great Comet” (Photos courtesy of Horizon Theatre)

Review: ‘Comet’ presents sexy parts of Tolstoy in constellation of musical talent

ALEXIS HAUK·NOVEMBER 2, 2023

“Leo Tolstoy: He’s a fizzy, dizzy good time!” That’s what one imagines a review of the verbose Russian author’s War and Peace might have read if critics of the late 19th century had only had Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812 — the electropop musical adaptation of just 70 pages of Tolstoy’s sweeping tome — to go from.

This effervescent, absorbing and musically versatile delight, playing at Horizon Theatre through November 26, cleverly gives us the sexier, more scandalous portion of Tolstoy’s 1867 epic quilt of narratives and philosophical musings set during the Napoleonic Wars.

Under the dexterous direction of Heidi McKerley and in the hands of a go-for-broke cast, it’s a production that, simply put, demonstrates what live theater at its best can do.

With a two-and-a-half-hour run time that somehow flies by faster than a comet’s tail, the story line follows a sweet but naïve young woman named Natasha (Alexandria Joy), who’s engaged to Andrey (Hayden Rowe, who also plays violin), the son of a prince who’s serving as a soldier in the far-off war.

Things soon go awry for Natasha and the soap opera-like soup of supporting characters swirling around their Moscow social scene. And why else? In the parlance of our times: A f***boi. Natasha meets and instantly falls for the magnetic charlatan Anatole (Jordan Patrick), setting off a Rube Goldberg of bad choices that ends, in true Russian fashion, in ruin and exile.

Finally, just to round out the rest of the titular characters, there’s also wealthy, unhappily married Pierre (Daniel Burns), the shy and frequently melancholy friend of Andrey’s, who was played by Josh Groban in the play’s Tony-winning Broadway iteration that ran in 2016 and 2017.

That’s a pared-down, very Wikipedia-entry-level description of what transpires — which leads me to one of the magic tricks of the show, which is how the excessive intricacies of the plot are acknowledged outright in the lyrics of the songs (It’s more like an opera in that virtually every line is sung.).

The very first number, appropriately titled “Prologue,” sets the tongue-in-cheek tone that pervades the evening, beginning somberly and slowly: “There’s a war going on / out there somewhere / and Andrey isn’t here.”

And then the ensemble pauses a beat, and the whole score shifts as they launch into a jaunty, vaudeville-like tune that directly addresses the audience and makes a Meta Meal out of our plight.

“And this is all in your program. You are at the opera. Gonna have to study up a little bit if you wanna keep with the plot,” the entire cast sings, smiles on their faces, swaying back and forth. “Cause it’s a complicated Russian novel. Everyone’s got nine different names. So look it up in your program; we’d appreciate it; thanks a lot. Da da da, da da da.”

The musical was first produced in 2012, then spent four years or so making the rounds at different theaters, including stagings in Quito, Ecuador, and in Massachusetts. After its celebrated run on Broadway, it was sadly beaten out for the Tony for Best Musical by Dear Evan Hansen, but hey, time will tell which one holds up better. (Spoiler: It’s this one.)

Creator Dave Malloy, who crafted the book, music and lyrics of the show, is no stranger to adapting literary giants. In 2019, he crafted a musical from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. And he also wrote the music and lyrics for a new musical adaptation of Roald Dahl’s The Witches, which opens in London this month. Keep an eye on this kid — he’s going places!

While Malloy’s writing is strong, this show is a heavy lift; its success relies on a strong cast and musical team. Thankfully, at Horizon, the stage is a crowded constellation of Atlanta musical theater talent who invite you in to bask in the glow of their artistry all the way through their final bow.

This is particularly true of Joy, a fresh but already familiar face who has appeared on stages across Metro Atlanta. Natasha finally grants Joy a role worthy of her gifts as a performer and, especially, as a vocalist. In the solo “No One Else,” for instance, she’s tasked with climbing around the entire set as she delivers a soaring piece on longing, envisioning what life might be like with Andrey, the uncertain promise of love and security. In a feat, Joy manages to almost make you forget that she’s moving at all as her voice carries us with her.

In a smart casting choice, Joy has been matched up again here with Patrick, her same toxic-love co-star from last year’s production of Heathers at Actor’s Express (Nothing more toxic than the literal poisoners Veronica and J.D.).

These two actors have a credible and crackling chemistry that makes their initial meet-and-flirt duet, “Natasha and Anatole,” captivating to watch. As does the lighting design by Mary Parker, which transforms the pivotal sequence visually into the tangled hormonal spider web in which these characters are now caught.

In the part of Anatole, Patrick gives one of the best physical comedy performances of the evening, skillfully playing up the irrepressible scumminess of the seducer while also winking at and skewering the trope of the irresistible bad boy. There’s not a comic facial expression that he hasn’t mastered, and this allows for a characterization that is simultaneously rooted in the play itself — while also very much in cahoots with the audience about the artifice of his schtick.

As Anatole’s scheming sister Helene, Janine Ayn serves up Real Housewives of Moscow energy and slams down some scorching vocals. As Natasha’s caring but confounded cousin, Anna Dvorak also delivers fine, sensitive work. Then, of course, there’s Daniel Burns as Pierre, the melancholy half-namesake of the show who anchors the entire piece with his soul.

Ultimately, the self-aware beats speckled throughout the show — and the diverting performances especially — remind us that even though this is big serious literature we’re witnessing, everyone’s here to entertain. And the spectacular entertainment does not stop. At one point in the show, the entire theater was shaking.

Is there a term for when a theater-going experience feels like riding a party bus? If so, insert that here. People were stomping in their seats, clapping and laughing and even singing along. It’s a rare thrill to feel breathless when you’ve hardly been moving at all — but that’s thankfully the very experience that an audience is in for when they go to see this strange and stunning show.

::

Alexis Hauk has written and edited for numerous newspapers, alt-weeklies, trade publications and national magazines, including Time, The Atlantic, Mental Floss, Uproxx and Washingtonian. Having grown up in Decatur, Alexis returned to Atlanta in 2018 after a decade living in Boston, Washington, D.C., New York City and Los Angeles. By day, she works in health communications. By night, she enjoys covering the arts and being Batman.