The History Behind HOW BLACK MOTHERS SAY I LOVE YOU

July 13th, 2018

Immigrant Domestic Workers and Family Separation

The phrase “family separation” has taken on new meaning in light of recent events surrounding immigrants and asylum-seekers to the United States. Though the specifics are different, How Black Mothers Say I Love You examines the repercussions of a similar separation for one family, and a path to healing and acceptance. Daphne, the mother in the play, would have come to North America under an immigration program that allowed her to do domestic work in order to earn citizenship. Programs like this often required women to be single, so bringing any children she may have had would be out of the question.

Playwright Trey Anthony originally set this play in Canada to reflect the stories of the women who were part of a Canadian government program that began in 1955. The West Indian Domestic Scheme recruited young women from select West Indian islands to satisfy the country’s need for post-war household labor. However, this scenario, of a mother emigrating to find work and create better opportunities for her family, was and is common all over the world.

Anthony herself comes from a legacy of black mothers who have left their children. She says, “My grandmother left her children in Jamaica and went to England and was separated from them for six years. My paternal grandmother also left her children in search of a better life. Both of my grandmothers were poor women mothering in less than ideal situations. The legacy of mothers leaving continued when my own mother left us in England in search of the Canadian dream. I was left behind… Even though my family is now reunited, we never fully recovered from these separations. We are women who share a complicated herstory of leaving and being left behind.”

The West Indian Domestic Scheme recruited young women from select West Indian islands and enlisted over 2,250 women who left their homes to assist thousands of upper class families in exchange for permanent residency. Due to Canada’s strict and often racially discriminatory immigration laws, the scheme was often the only opportunity for women to migrate to Canada in order to better their families’ lives. By their own accounts, while leaving their children caused them immense sorrow, many of these women felt they had no choice.

Women intending to participate in the scheme submitted an application through their country’s Ministry of Labour. Applicants were required to meet four criteria: they must have been between the ages of 18-35, must have been single, must have received at least an eighth grade education, and must have passed an interview and medical examination conducted by Canadian immigration officers. Once granted access to the program, the women were required to serve one year as a domestic worker earning a salary of $280. Only then could they send for immediate family members and pursue more prestigious job opportunities.

Upon their arrival, migrants were often literally and figuratively isolated from each other and the surrounding community. According to a study conducted by social researcher and anthropologist Frances Henry, many women felt they were unprepared for the isolating, demeaning, and strenuous way of life. While some women expressed a positive experience, the majority of those interviewed cited instances in which they were personally discriminated against. For this reason, many women were forced to continue working as domestic employees for years after their service ended; no established business hired people of color. Racial bigotry at times led women to leave their children in the West Indies permanently to spare them a childhood of alienation.

Brief History of Immigration Legislation in the United States

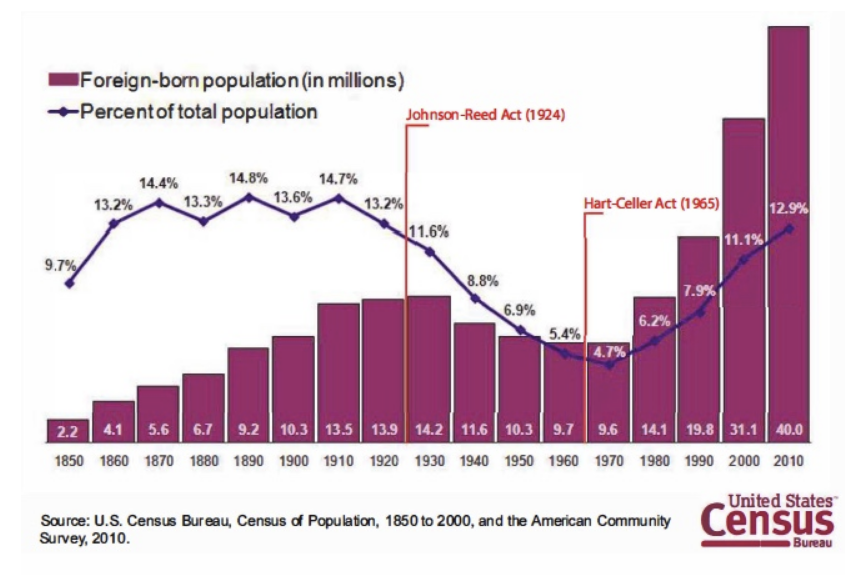

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed a landmark immigration reform bill, the Hart-Celler Act, into law. It abolished the quota system that had been established by the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which critics condemned as a racist contradiction of fundamental American values. For example, the Johnson-Reed Act is the legislation that prevented any citizens from Japan from entering the United States.

By liberalizing the rules for immigration, especially by prioritizing family reunification, the Hart-Celler act stimulated rapid growth of immigration numbers. Once immigrants had naturalized, they were able to sponsor relatives in their native lands in an ever-lengthening migratory process called chain migration, which is an enduring legacy of Hart-Celler that is a significant part of the immigration conversation today.

Unlike flows from other parts of the world, the uptick in Caribbean immigration was not necessarily prompted by the 1965 Hart-Celler Act because migration from the Western Hemisphere had not been subject to the national origin quotas set in 1924. Instead, the growth had to do with circumstances specific to each country. Migration from Jamaica and other former British colonies was driven by immigration restrictions set by the United Kingdom and the simultaneous recruitment by the United States of English-speaking workers of varying skill levels, from rural laborers to domestic workers to nurses. At present, Jamaicans are the largest group of American immigrants from the English-speaking Caribbean.